Malcolm Walker

Escape from Nottingham

The ‘coming out’ stories that are easiest to share are short, dramatic, and uplifting. But for boys growing up in the provinces in the 1960’s who would grow up to be gay, the awareness of being gay was something they grew up with, which at best they were unable to label, and at worst it had dark sides they were unable to account for.

My earliest awareness of imagining of what ‘gay feelings’ were started from me being aged 10. The culture I grew up in was a small town in the midlands. Life there was centred around family values-often projected via light entertainment on television. There I had light fantasy ‘crushes’ on the bearded men who appeared on the screen for any length of time, across the schedules. I did not admit to having these feelings to anyone. My parents were the only people I might have confided in, and they saw television as their electronic childminder, where they thought less about the images the screen presented, and more about how they might get other jobs done with less need to be watchful.

A homosexual life was a logical impossibility; family values said so by saying nothing about it. Family values also said that there was no life outside of the family. I had no material with which to imagine how a life outside of my family might work. But the signs that all might not be well were already present in my family, where they were ignored. I had a distant father, and a mother who more than made up for his distance from me, well from all of us, by making sure that I stayed close to her. If she had not stayed close to me then none of my family would have. The models of masculinity that I saw around me used adult images of drinking and smoking as badges of honour/membership and macho signs of entitlement. At age 7 or 8 the nearest I got to such an identity was going to the sweet shop to buy Old Holborn tobacco and cigarette papers for my dad where my age made it illegal for me to buy tobacco but the confectioner knew my dad. Being dads errand boy was as close as I was going to get to being acknowledged by him. At least it was a role.

My mother ran errands for elderly neighbours, including doing their weekly shop whilst doing the family weekly shop. The unpaid errand boy script repeated itself in how I related to her. From the age where I was tall enough, she would put me in charge of pulling the shopping trolley or carrying the bags as she led the charge around the shops. This earned me some horrible teasing in primary school that I could neither deny nor rebut.The teasing came from pupils who saw me when they were following their mothers around the shops, where their mothers were doing what my mother was doing, shopping, but for fewer people. They did not have to carry anything. Thinking of it now, their teasing of me was them claiming some detachment from their mothers that they did not actually have, where I could not think fast enough to point out to them their denial.

In the 2020’s there are plenty of stories where the young adults of today relate accounts in the popular media where they explain how as teenagers they were introduced to drugs, where they knew too little about sex to stop the non consensual sex that followed. There then follows comments about trauma, confusion and difficulty forming long term relationships as a result of the non consensual sex.. When publishers share these stories they often preface them with comments that suggest they are rare, if not unique, until they publish the next similar narrative, and make the same claim.

Such stories are as old as the drugs themselves, including NHS medicines, I have my own version of that narrative which if I explained it, and how it was disguised, I would not be believed.

I don’t know how I navigated my teenage years. However I did it, it was much more through amnesia, and the absence of language, than it was through formal education. The teenage reasoning I am at ease with sharing is how as a teenager I believed that I was gay because I liked David Bowie, who was highly popular back then. But that ascribes more influence to the power of popular music than the evidence would support. But Bowie was to music what Dr Who was to television. Both went through identities at a speed that surprised the public. Both started in the early 1960’s. With each new identity they both left behind clues to a mythology that complemented their multiple previous identities, which gave them a lot of airtime to expand on their pasts. Fine material for a teenage boy to pin his hopes on, where they could ignore any mysterious undertow in their own lives where they had not the language to explain why they were where they were. Back then a lot of life went by unexplained.

I discovered cottaging at the age of 17, and I was always the youngest among the married men who did not want to go home quite so soon to their wives. If my cottaging was proof of some personal discomfort within me, then I got out of the habit of it very gradually, by breaking my ‘coming out’ into manageable stages, from the age of 25 onward.

The first stage was the argument I had with my family about their choice of my teenage schooling, where I was not allowed to think that I was deliberately being taught practically nothing. Where I disagreed with them most was how their idea of schooling had put my life ‘on hold’ for the duration of it, and a long time afterwards, where saying nothing let the malaise continue.

The second stage of my coming out was to give myself space in the small town far enough away from the tightness of family life so that I could begin to breathe and choose my friends for how reliable they were. In all of my family life I had seen Mother make few close friends outside of family, and until I set myself some distance from family I could see myself doing the same.

The third stage came three years later when I left my home town, and moved to Nottingham. For four years I lived and worked doing last-in first-out low paid jobs there, between bouts of unemployment. In 1989 this led me into being in therapy for the first time. That led to a much needed rethink, where ‘coming out’ seemed possible but there was no clear path as to how to do it. Later when I asked for more therapy I was put on an NHS waiting for my second course of therapy. That gave me an unexpected path. When I got put on the waiting list I could not wait. So to relieve the pressure of my need I started what is nowadays known as journaling.

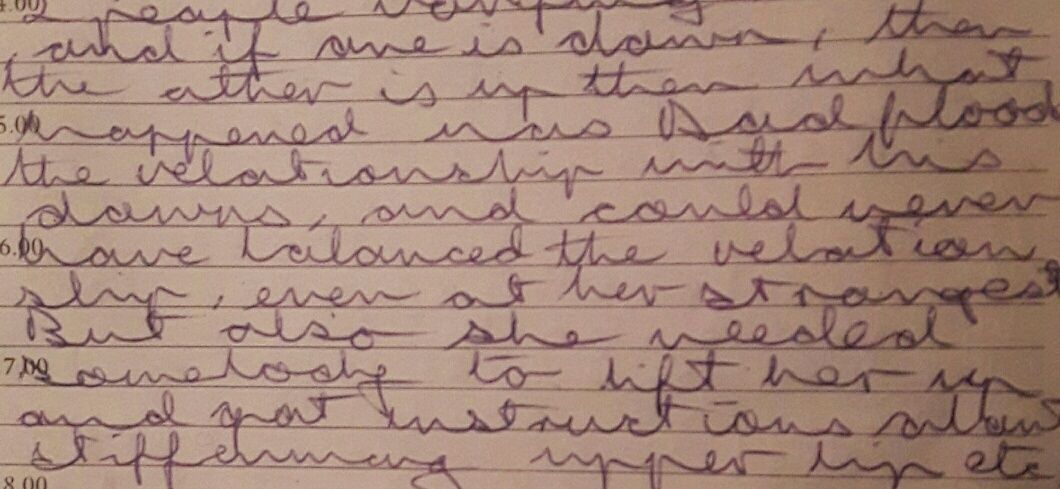

Every night for twenty months I wrote my thoughts down in an A4 pad, to clear my head enough for me to sleep better that night. The average length of a day’s entry was four sides of A4 foolscap. Some day’s entries were longer. The journaling kept me more sane and calm than I would otherwise have been.

It got me nearer being ‘out’ as being gay. But what it proved to me most was that I needed to meet a gay man who I could talk to and he would listen to me asking about what ‘being gay’ was supposed to be about. I needed to meet them well outside of the rudimentary ‘secrecy’/not speaking that I shared with those I, now less frequently, cottaged with. .

When one lonely Saturday night a handsome gentleman broke the code of silence that the toilets maintained, by thanking me by name at the end of the time with him, the loss of anonymity scared me. But with a lot of journaling I took that fear in my stride and realised that a rethink and a radical change of course was required. I was still waiting for the doctor’s appointment for the second lot of therapy. I knew nothing about gay bars and had been told ‘They are very lonely places’ by a Christian I knew. When I was told that I should have replied to the Christian who said it ‘Not nearly as lonely as cottaging is.‘, but I did not have the confidence with which to open that flood gate of great hurt and disguised neediness with somebody I could sense it was unwise to be too open with anyway.

I barely knew about Nottingham Gay Helpline, and knew nothing of the other ways the gay world networked. With my journaling I reached for the idea that if I really wanted not to cottage again, then I had to use it as a springboard for a talk, live, to a gay person.

The only time I had knowingly talked to a gay person who was ‘out’ before was during the government leaflet drop for the aids crisis, when I rang the London gay helpline and the person on the other end was rather dismissive of me wanting to ‘Come out’ amid the wall to wall undeclared small town homophobia that he could not understand. That was the mid 1980s. By 1992 I had come a long way towards taking the sense of tragedy and loss of opportunity to connect out of sexual secrecy. I had journaled quite a lot about how silence=secrecy, and secrecy=silence where I had unpicked how each fed into the other and formed a doom loop to maintain each other. I was fifteen months into the journaling in lieu of therapy, on the cold of 9th of Feb, 1992, when I cottaged in the willy shrinking weather that night, I unexpectedly found a person not for sex but to actually talk to.

Russell was his name and he was a ginger bear. We talked that night and walked to The Admiral Duncan for a drink. We met again on the Friday Valentine night special. Over the next four months I supplied most of the attachment as he tried to teach me what passed for the etiquette of being gay in Nottingham in 1992 and we both tried to make it seem as if that was love. He ended the relationship because I had too much personal baggage to reward his patience with me. I don’t think ill of him for it. I thought I was ‘out’ but I was not. I did what a lot of gay men were doing, when they took each other at a face value in a way that was unsustainable after a short while.

Through Russell I found my exit from Nottingham. I found what I really did think of as love. Whatever name it should have, I worked at it, and it has proved durable. Eventually, with a lot of help, I moved to rent a house in rural Northern Ireland in a move that was counter-intuitive. Because nearly no gay men moved from England to Northern Ireland, which was famous for a certain shouty preacher. If there was movement, the direction of travel across England was the same as it was from Belfast - towards London because London was the gay capital of all Europe at the time.

It would be a very long time before I joined all the dots, from being gay, through to where ‘coming out’ included learning how much mental health mattered whatever sexual label anyone wanted to own. They were whole decades where I had lived and travelled in hope, but I was slow to recognise where I had arrived, and where I might go next.